The Rev. Noah Van Niel

The Chapel of the Cross

March 17th, 2019

Year C: Genesis 15:1-12,17-18; Psalm 27; Philippians 3:17-4:1; Luke 13:31-35

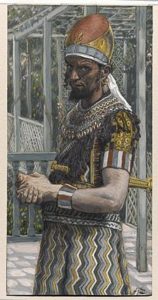

There are two Herods. There were actually two Herods who factored into Jesus life. You would be forgiven for not knowing this though, because the Gospels refer to them both as “Herod.” The first Herod was “Herod the Great,” and to many he was just that: a war hero, tight with the Roman luminaries Mark Antony and Octavian Augustus. Proclaimed King of the Jewish people by the Roman Senate, he ruled over the province of Judea for 37 years. He expanded the Temple, and undertook other impressive, large-scale building projects. He was tyrannical and he was feared but he was successful by many measures. This was the Herod who ordered the slaughter of every baby in Bethlehem when the Magi gave him the slip after visiting the baby Jesus. He was a ruthless, but he was legendary.

This is not the Herod we hear about in today’s Gospel passage. Today Jesus is talking about Herod the Great’s son, Herod Antipas, a name which comes from the Greek for “like the Father.” This was not an uncommon surname for rulers at this time, but in his case it’s something of an ironic moniker. Compared to his father, Herod Antipas was a weak ruler. He wanted to play the tough guy, like his Dad, but he doesn’t seem to have been able to pull it off. He was the kind of guy who stole his brother’s wife. He was the kind of guy who imprisoned John the Baptist but didn’t actually kill him until he got drunk and his step-daughter Salome did her famous dance for him after which she demanded John’s head on a platter. In fact he didn’t even get to inherit his father’s entire kingdom, he only got the countryside of Galilee and Perea, while his brother got the crown jewel of Judea which included Jerusalem.

It was because he was the ruler over Galilee, though, that Jesus was familiar with what kind of man this Herod Antipas really was. And frankly, he wasn’t too impressed. “Some Pharisees came and said to Jesus, ‘Get away from here, for Herod wants to kill you.’ He said to them, ‘Go and tell that fox for me, ‘Listen, I am casting out demons and performing cures today and tomorrow, and on the third day I finish my work.’” Jesus is calling Herod’s bluff. He’s telling him, “You want me, come and get me.” And as was typical of his behavior, Herod backs down; he was all bark, and no bite. And we don’t hear anything else from him until Jesus’ trial, when Pilate, eager not to get embroiled in this provincial skirmish, sends Jesus to Herod, who, true to his nature, mocks him, flogs him but sends him right back to Pilate to actually carry out the sentence.

Now I’m not saying I wish Herod Antipas was a more ruthless leader like his father. Lord knows we don’t need any more glorification of violence in our world right now, after what happened in New Zealand. But what amazes me from this story is Jesus’ ability to see through people and know exactly who he’s dealing with. He knew Herod Jr., unlike his father, wasn’t going to kill him even though the Pharisees clearly thought he would. He’s not fooled by the bluff and the bluster, the titles and the trappings. He knew Herod Antipas was more sleaze than slaughter. As it says in the second chapter of the Gospel of John, “[Jesus] knew what was in everyone.” (John 2:25).

But Herod Antipas is not the only one pretending to be someone he is not. Too often we fall into that category as well. An inordinate amount of our life is spent constructing what I would call a false self, a façade we present to the world to hide (and protect) our true selves. I don’t mean that who I am when I’m wrestling on the floor with my kids is who I should be in an important meeting at the office is who I should be when I’m socializing at a cocktail party. Those are different aspects of a personality, getting played out, appropriately, in different social scenarios. No, our false selves are those narratives that come from outside of us, images or ideas we aspire to because we think that’s how we are supposed to act, or look, or think. We get these messages from all over: popular culture, upbringing, professional enterprise, or various other external sources. This inclination of ours towards promoting our false self over our real self has only been exacerbated through technology and social media which makes it dangerously easy to broadcast a highly curated version of our life to the world. And this only makes the obfuscation of the truth easier and lies harder to spot. Somehow the thing that was supposed to make the world more connected has just made it more fake. And this is taking its toll on people: research has shown that following endless streams of Instagram stories or Facebook posts about the “perfect” life that others have is increasing depression and anxiety in people. This is all just an amplification of that archetype that Herod Antipas exemplified: a whole lot of bluff and bluster put on so that no one has to be real, and everyone can pretend to be the person that no one is, but everyone wants to be thought of as. And after a while we can spend so much time keeping up appearances, online or off, that we lose touch to who it is we really are, or were, to begin with.

Esse quam videri. You’re familiar with this phrase? Esse quam videri. It’s our North Carolina state motto. And do you know what it means? Translated from the Latin it means, “to be rather than to seem.” It’s taken from Cicero’s essay On Friendship, a chapter in which Cicero is bemoaning how not nearly so many people actually want to be virtuous as want to seem to be virtuous. Even the ancient Romans, apparently, would rather be fake than real. And where this is really damaging, Cicero notes, is in our relationships. Falsehood is no basis for friendship, Cicero argues. If you want friendship, if you want a real relationship, it needs to be based on truth, authenticity, honesty. When it comes to our connections with others, it is to be that matters, not to seem.

But it’s not just our relationships with other people that are threatened when we start from a place of falsity, it’s our relationship with Jesus as well. If we want to have a real relationship with Jesus, we need to be honest with him; we need to be real with him. One of the reasons for that is because, while it may be possible to fool other people about who we really are, like I said before, it’s not possible to fool Jesus. He could see right through Herod Antipas and he can see right through us, right into our hearts, and knows us as well, if not better than we know ourselves. So to try and build a relationship with him based on who we think we should be rather than who we really are is a non-starter.

But to lead with our false self when interacting with Jesus is not just pointless because he knows our real self anyway. The real problem is that it prevents us from receiving the benefits and blessings that he offers to those who come to him with honest and open hearts. In that same chapter in On Friendship from which our state motto is taken, Cicero talks about the fact that in friendship, unless you lead with truth you will not receive truth, “unless…you see an open bosom and show your own you can have nothing worthy of confidence, nothing of which you can feel certain, not even the fact of your loving or being loved, since you are ignorant of what either really is.” We won’t know honesty until we act honestly. We won’t know love unless we show love. We won’t know Jesus until we show ourselves, our real selves. And yes, this is scary, because our real selves are nowhere near the pristine or perfect façade we hold up to the world. And the fear of judgment, or rejection, or ridicule that we have learned from our fellow human beings can keep us from opening up. But while it may be risky to open our hearts to other people, it is not a risk with Jesus. We are safe to open our hearts to him because he first opened his heart to us. He’s already taken the risk on our behalf. We can be assured that he knows and loves and forgives that true you because he initiated this friendship with an act of honesty, vulnerability and love upon the cross. That is where we can find the confidence, the certainty, the courage to let down our guard and let him in.

If we long for authentic relationship with Jesus Christ we need to start with our real selves, not our false selves; from a place of truth, not lies. Lent is as good a time as any to start this process because Lent is a season of truth telling: of us telling the truth to God through our confession and repentance, and of us having the truth of God re-told to us in the passion of Jesus Christ: the truths of forgiveness, mercy and love that are so apparent in his life and death. Confronting the truth of who we really are will force us to tear down all those exhausting facades we have erected to navigate the niceties of daily living; it will force us to bring to light those ugly bits of ourselves so that we may be washed clean of our imperfections, and emboldened in our blessedness. Because that same light that reveals us our not-so-secret failings and insecurities also can help us uncover those parts of ourselves that are so tender, so beautiful, so personal that we haven’t yet been brave enough to show them to the world. As with a real friendship, a real relationship with Jesus promises both to show us the ways in which we are falling short of being the person we are capable of being, and the ways in which we have more to offer this world than we might actually even know. Do not let the false narratives of who you should be, get confused with the real narrative of who you actually are. If you long to know Jesus, tell the truth. Open wide your heart to him, not for his sake, but for yours. And do not be afraid. For as he learned when he opened wide his heart to us upon the cross, when we offer to God the fullness of our beautiful, broken selves they will not be rejected, they will be resurrected. Amen.