The Rev. Noah Van Niel

The Chapel of the Cross

June 16th, 2019

Trinity Sunday (C): Proverbs 8:1-4, 22-31; Psalm 8; Romans 5:1-5; John 16: 12-15

The title of my master’s thesis was “Credo, Credimus: I believe; We believe,” and its organizing question was “What is the role of doctrine in The Episcopal Church today?” This was a live question when I wrote it and yet somehow, even with this work of sparkling scholarship, the question remains far from settled. This is probably because my mom was the only one who read it. But the fact is, I continue to hear people talking about doctrines as antiquated, or even counter-productive to living the life of faith and building the Kingdom of God. People would much rather get busy living a good life than waste time and energy on arcane theological formulations. Because our creeds and other statements of faith are man-made and not God-given they are seen as getting in the way of just following Jesus. And so an increasing number of people are simply done with doctrine.

And not without good reasons. When people say they want to get rid of doctrine it is often a reaction against those who cling so tightly to the teachings of the church that they turn Christianity into a private club you can only gain access to if you know the right passwords. Don’t know the difference between Incarnation and Incantation? Keep on walking. Do you get your epiclesis and your anamnesis mixed up? Might as well not even bother. Can’t spell Nicaea? See ya! The reality is people often use doctrines to make the Church an institution of exclusion, not inclusion.

And within the Church the situation isn’t much better. Doctrine has been (and still is) a point of division and discord; the thing that splits us apart rather than brings us together. Throughout Christian history people have used doctrinal differences as an excuse to question others faith, kick them out of Church, or even kill them. Doctrine is the thing we argue about, fight about, split up over, spill blood over and as such it seems antithetical to the Kingdom of Heaven.

And then there’s the problematic practice of some of our traditions that says all you have to do is say you believe certain things and then you would be “right” or “saved.” This is how some people have taken Paul’s words in the letter to the Romans when he says all we need to do is to say we believe in Jesus Christ and we will be “justified by our faith.” The erroneous assumption being that the way those beliefs shaped your life was less important than getting them correct. This ultimately leads to people whose lives don’t match their lips—turning them into pharisaical hypocrites, and emptying the doctrines of any meaning.

I am, in large part, sympathetic to these grievances. Measured in these ways doctrine is a major hindrance to living a faithful life. But I worry that the kind of thinking that says we should do away with the doctrines completely, in the name of action (well-intentioned and necessary though it is) presents a false and ultimately unhelpful dichotomy. Because the relationship between right belief (orthodoxy) and right practice (orthopraxis) warrants a more subtle understanding than that, and need not be a zero sum game. Yes, doctrine was and is misused and abused throughout Christendom. But we can’t just disregard our statements of belief as being unimportant, or even less important than the life one leads because the fact is the beliefs to which you subscribe, unavoidably shape the kind of person you are. We need the Golden Rule to determine a definition of “good.” We need Jesus to show us what it actually means when we say “love your neighbor as yourself.” And, as you have heard me say before, the root of the verb “to believe” originally meant “to hold dear.” To believe something was to love it, to cherish it. And this means much more than just knowing it or reciting it, it means living it.

For example, I could say, “I love you” to my wife all day long, but if I never did the dishes after she cooked dinner, or never bought her a present on her birthday, or never kissed her goodnight, my words would be empty statements; the right thing to say, but with no substance to back them up. So just as to love a person is not merely to say it but to show it, so too it is to believe something. When we separate these two things, belief and practice, we are already on the wrong track. They are intimately intertwined; complimentary parts that make up a coherent life of faith. Doctrines don’t give us all the answers, but they do give us enough structure to fashion a life around so that we don’t drown in an existential sea of ambivalence, meaninglessness or relativism. They hold us accountable to standards beyond just our own feelings and intuitions. And they offer us direction by seeking to reveal to us something true about the nature of the world and our place in it. But we have to hold them gently not with a stranglehold; we have to steer clear of enshrining them and instead give them room to breathe so that our understanding and application of those doctrines can unfold and evolve over time. This is a tricky balance to strike—to take them seriously enough that we can orient our lives around them, but not so seriously that we turn them into idols.

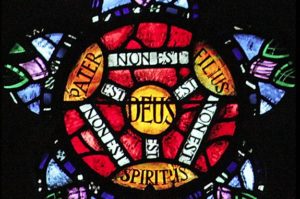

As an example, let’s take the doctrine of the Trinity. Today is marked in the Church as Trinity Sunday; the day we celebrate the majesty of the triune God—that is one God in three persons: the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. It’s the only feast day in the Church dedicated entirely to a doctrine. I heard a joke last week from someone in the parish that there’s a hidden clause in a priest’s contract that says there is a bonus to be had if they are able to actually explain the Trinity in an understandable way. It’s only half a joke. For the doctrine of the Trinity is one over which much ink and blood has been spilled, and it remains virtually impossible to comprehend. All the criticisms of doctrine I outlined above apply to the doctrine of the Trinity, as well. And yet it still does point us to some essential truths about God that can and should impact the good lives we are so keen to live.

The first of those truths is that at the center of our faith there sits a mystery. This tells us there are limits to our understanding of God. If we had a perfect mathematical equation at the heart of our faith it would lead us to believe we had God pegged, all figured out, fully comprehended and controlled. But instead we have an equation that just can’t compute: 1+1+1=1. To say God exists in three persons is to say that God has acted in these three manifestations—Father, Son and Holy Spirit—and yet is still one God and we don’t exactly know how. This posture of humility lets us know that there is more truth that we don’t yet know. This is precisely Jesus’ point to his disciples in the Gospel today, when he says to them, “I still have many things to say to you, but you cannot bear them now. When the Spirit of truth comes, he will guide you into all the truth,” meaning he’s not done yet. And so we are left to bow to the infinite, not the definite; to submit in wonder and awe to the Truth that God is more than we can ever fully know or explain. God as mystery—within our reach but beyond our grasp—that’s truth number one from the Trinity.

The Trinity also tells us that God is relationship. God is not independent or isolated. God reaches out. God’s work is inherently one of connection; a cycle of giving and receiving. Our one God overflowed into the natural creation becoming what we might call, it’s Father; that same God reached out in flesh and blood to that world, in Jesus Christ, the Son, and God continues to pour into our hearts through the Holy Spirit. The Trinity teaches us that God is in God’s self a community, a web of relationship, and therefore as His followers, we are called to be in relationship with one another.

And finally the Trinity tells us that the nature of this relationship, this connection between the persons of the Trinity and between them and the world is love. Love is the tie that binds Father to Son to Holy Spirit. It’s the current running through that divine triangle. God so loved the world that he gave his only begotten Son, and his only begotten son so loved the world he died for it and sent it the Holy Spirit to guard and guide after he was gone. It’s not about order of place, or hierarchy or time in history, the Trinity is about love, and, as faithful Trinitarians, we should be too.

Mystery. Relationship. Love. These are some fundamental Christian truths to which the doctrine of Trinity is pointing us that can and should instruct our life. God as majestic mystery, this humbles us and lets us embrace the world with openness, not arrogance. God as communal, generous, giving; this calls us out of ourselves and into relationship. The persons of the Trinity connected to each other and to us through love: this tells us the attitude with which we should interact with all of creation. There’s more to glean here, for sure, but what I hope is becoming clear is that theology matters, because the doctrine of the Trinity tells us things about God that, if we believe them, if we cherish them, will shape what we do with our lives. We cannot separate what we hold dear from who we are.

So to all those who are done with doctrine remember this: what you do with your life depends on the things you believe to be true, the things you hold to be sacred. To the extent that doctrines serve as a shibboleth –a test to determine who is in and who is out of the group—they are idols that need to be smashed. To the extent that doctrines are an intellectual exercise alone, they are empty. To the extent that doctrines are taken to be the last word on the reality of God, they are dead. But doctrines should not be discarded, just as they should not be worshipped. They should be lived and loved. For only then shall they be true. Without attempts at explaining things like the Trinity, without the slavish labors of theologians and scholars, contentious though they may be, we’d be completely in the dark. Instead, we have the candlelight of the creeds and other statements of faith to illumine our path. For through them we know something of the substance of God and this in turn forms the substance of our lives. So that’s why, as Christians, everything we do in life, we do in the name of the Father, and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit; because when we say “We believe,” what we are really saying, is, “This is who we are.”

So in that Spirit, would you please stand and say with me: “We believe in One God…..”