The Rev. Noah Van Niel

December 23rd, 2018

Chapel of the Cross, Chapel Hill, NC

Advent IV (C): Micah 5:2-5a; Psalm 80:1-7; Hebrews 10:5-10; Luke 1:39-55

People get ready there’s a train comin’

You don’t need no baggage, you just get on board

All you need is faith to hear the diesels hummin’

You don’t need no ticket, you just thank the Lord.

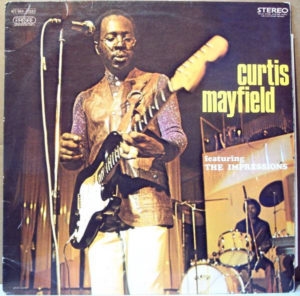

That’s an opening I learned in a Gospel choir I was in in college which led into an a capella version of the 1965 song “People Get Ready” by Curtis Mayfield and The Impressions,  which is arguably one of the most famous songs of the civil rights era, and unarguably one of the most covered songs of the past 50 years. I even noticed it serves as the title to a current contemporary art exhibit at the Nasher Museum over at Duke—I know, “booooo Duke,” but the exhibit sounds pretty interesting. I often find myself humming this song this time of year because I think it’s a pretty good summation of the Advent season: “People get ready there’s a train coming…[and] All you need is faith to hear the diesels hummin.” They are words of change and challenge; of preparation and expectation. Sounds like an Advent anthem to me. So I like this song except for one thing: it makes faith sound a little too easy. He’s not wrong exactly—all you need is faith to get on board with God, as St. Paul says, we are justified by faith—and yet the way Mayfield puts it, and the way Paul often talks about it, makes faith sound a little too simple, like just stepping onto a train.

which is arguably one of the most famous songs of the civil rights era, and unarguably one of the most covered songs of the past 50 years. I even noticed it serves as the title to a current contemporary art exhibit at the Nasher Museum over at Duke—I know, “booooo Duke,” but the exhibit sounds pretty interesting. I often find myself humming this song this time of year because I think it’s a pretty good summation of the Advent season: “People get ready there’s a train coming…[and] All you need is faith to hear the diesels hummin.” They are words of change and challenge; of preparation and expectation. Sounds like an Advent anthem to me. So I like this song except for one thing: it makes faith sound a little too easy. He’s not wrong exactly—all you need is faith to get on board with God, as St. Paul says, we are justified by faith—and yet the way Mayfield puts it, and the way Paul often talks about it, makes faith sound a little too simple, like just stepping onto a train.

In my experience faith is not a simple thing. It’s more like running after a moving train and using every ounce of your strength to pull yourself on board. But Curtis Mayfield is hardly alone in making it sound so, we do it all the time: “Have a little faith,” or “keep the faith,” or “I’ve got faith in you.” Such colloquial phrases have perhaps allowed us to skim over just how preposterous, how ridiculous, how sometimes impossibly hard it is to have faith, and to keep it.

I find it helpful, when talking about faith to remember that, according to the religious scholar W.C. Smith, the German root of the verb “to believe” could be translated more closely as, “to hold dear,” or more forcefully, “to love.” Like love, faith is the act of giving of one’s heart and mind to something, like in a relationship, and then orienting your life around this relationship in such a way that you live hopeful that this thing will hold up, but not being able to know for sure that you are correct.[1] Thinking of faith in this way, as a commitment to an idea which we hold dear, means that faith depends on trust just as much as it does on truth. It is a way of living and engaging the world that is based on promises, not proofs. And that means it’s not as easy, or as clear cut as we might like it to be.

But the fact is we build our lives, not just our religious lives, but our whole lives, on the foundation of promises in which we put an inordinate amount of faith, so this is not as foreign an idea as it may seem. Our family lives are based on the vows of, “Till death do us part.” Our justice system is based on swearing “I solemnly swear to tell the truth, the whole truth and nothing but the truth.” Our medical system is based on Hippocratic oaths that the woman with the scalpel standing over your unconscious body means you no harm. Even the rules of the road are based on believing in the very important promise that I will drive 70 mph over here in my little metal box with wheels that holds the potential for fiery explosion, and you will drive ten feet away at 70 mph in your little box, and everything will be fine because I believe, I have faith, you will stay in your lane and I will stay in mine. We know what it is to live on promises, not proof.

And yet when it comes to our faith in God’s promises we can have trouble assenting to the terms; we can struggle to believe that God can do what God says God will do because often the promises just seem too impossible, too preposterous, too unlikely to ever come to fruition.

But our God is a God of preposterous promises. Ridiculous, impossible promises. Always has been, always will be. Remember Abraham and the promise that his descendants would be more numerous than the stars? Sounded like a joke to him and his wife Sarah because they were old and barren. And yet, it was so. Remember Moses, and those preposterous, impossible promises about freedom from slavery in Egypt, and water in the wilderness, and lands flowing with milk and honey? And yet it was so. Preposterous promises to women like Hannah the mother of Samuel and David, the shepherd boy who would be King. And despite all the odds they are brought to pass. Over and over through history God is making and fulfilling preposterous promises. And the question is whether God’s people will have faith in those promises coming true, give themselves to them, hold them dear or whether they will give up on them and allow the preposterous-ness of those promises to snuff out any hope for their fulfillment.

One of the people prophesying preposterous promises for God was Micah. Micah was active in the 8th century BC, a tumultuous time in the history of the people of Israel. The Assyrians had conquered the Northern Kingdoms, and now they had turned their sights on Jerusalem and the kingdom of Judah. Under siege, Micah recites the preposterous promise of God which we heard in our Old Testament lesson this morning that out of Bethlehem, of all places, there would come forth a ruler that would save God’s people and fend off the enemies at the gate. People thought this ruler would be King Hezekiah when he took over the throne and held off the Assyrians for fourteen years, yes, perhaps this was the one God was talking about, the one who would restore the fortunes of Israel and bring about a reign of peace! But in 701 Judah was overrun by the Assyrians and while Jerusalem was not destroyed, the people were conquered and lived as captives for years to come. And Micah’s preposterous prophesy is left dangling in the air as Israel waits and watches for salvation and restoration, through multiple eras of occupation, and exile. Which is why the cry through their history becomes “Restore us, O God of hosts; show us the light of your countenance and we shall be saved!” God’s promise fades to an ember glow, its preposterous-ness overshadowing its hopefulness.

But then, 700 years later, in a little town called Nazareth, many miles to the north of Jerusalem and Bethlehem; under yet another round of foreign occupation, an angel comes to a young Israelite woman named Mary. And he tells her that she is going to become pregnant by the Holy Spirit and the child she would bear would be the Son of God and he would be the one to restore the Kingdom of Israel, and sit on the throne of David. Talk about preposterous promises. But Mary doesn’t think it’s so preposterous. Confusing, Yes. Dangerous, yes. More than a little unorthodox, yes. But she knows the preposterous promises that God has kept through her people’s history starting all the way back with her ancestor Abraham. She has heard tell of God’s mercy on those who feared him in every generation. She knows stories of the powerful being brought low and the lowly being lifted up, how God has filled the hungry with good things and more than once sent the rich empty away. She knows of God’s help for his servant Israel, according to the promise he made to Abraham, and so she sings of it, and she sings of it because she believes in it. She believes that, as the angel says to her, “Nothing shall be impossible with God.” And in so doing she revives Micah’s prophecy, for after nine months, circumstances bring her to Bethlehem, the unlikeliest of towns, giving birth in a barn, the unlikeliest of locations, to the one who is “from ancient days,” who truly is “the one of peace.” And God’s preposterous promise, spoken through the prophet those many years before, is given new mean ing and new life.

ing and new life.

Mary is for us a model of real faithfulness, not of easy, simple faith but of ridiculous, preposterous faith. When Elizabeth greets her with shouts of joy and a leaping baby in her womb, she cries “Mary! Blessed art thou among women,” –why? Because “blessed is she who believed that there would be a fulfillment of what was spoken to her by the Lord.” Blessed are you because you believed, Mary, you had faith in the promises of God no matter how unlikely they seemed. Mary knew that unlikeliness is God’s favorite entry point. Always has been, always will be. The more unlikely the better. The wilderness; a barren or virgin womb; captivity and occupation; in a manger, in a stable, to unwed parents in a backwards town, these are the unlikeliest of circumstances for divine intervention, and yet they are precisely the places where God’s promises come true. And so despite the supreme unlikeliness of what was told to her, she believed. She gave her heart to this promise unable to understand or explain it or even see where it was going to lead, and God gave her a Son, Jesus, the Christ, who was God with us.

What preposterous promise is God giving you as a present this Christmas? What thing are you hoping for but you just can’t quite believe is even possible? Is it peace on earth? Good-will among all human kind? Joy to the world rather than fear and hatred? Maybe it’s more personal: healing from illness or infirmity. Reconciliation in a ruptured relationship. Happiness in the fog of depression. Let’s be honest, some days those promises can sound even more preposterous than a virgin birth. To some people, living by faith in preposterous promises will seem like foolishness. There is, after all, so much evidence to overwhelm any hopefulness for these promises ever coming true. But living by faith isn’t foolish. It’s courageous. And if that’s the kind of faith Curtis Mayfield is talking about, then I can really get on board, then I can really sing with him, “All you need is faith,” because that’s the kind of faith will need all of you. It’s the kind of faith that asks us look out at the world, or at our lives, and see the places of such barrenness, such brokenness, such impossibility and unlikeliness and trust, believe, have faith, that they are exactly the places where God is about to be born. Amen.

[1] W.C. Smith, Faith and Belief, Princeton University Press, Princeton NJ, 1979.