The Rev. Noah Van Niel

Christ and St. Luke’s

August 28th, 2022

Proper 17 (C): Sirach 10:12-18; Psalm 112; Hebrews 13:1-8; 15-16; Luke 14:1, 7-14

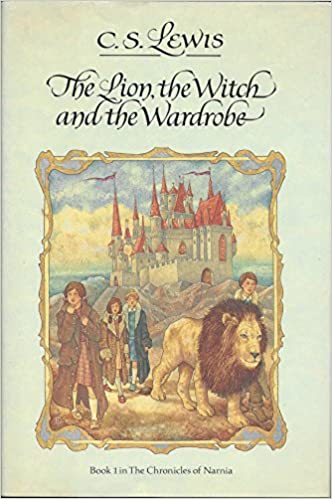

In our house we have recently begun reading the Chronicles of Narnia, by C.S. Lewis, to my oldest son. This is a parenting milestone I have long looked forward to since one of my most vivid and fondest childhood memories was having my father read those same stories to me when I was a boy. Though it comes second in the narrative order of the books, we have begun with the first composed and most famous of the septet, The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe. It has been so much fun to enter back into that magical world with Peter, Susan, Edmund and Lucy; a world that is at once strange and familiar, which is so often the case when we revisit something from our past later on in life. The story is unchanged, but we have changed, and so we experience it as new and old at the same time. I was also excited to revisit these stories because it was only in my 20’s that I learned Lewis had written them as Christian allegories, and given my current occupation, I was curious to see where and how those themes would reveal themselves.

On this visit back to Narnia, I was struck that while much of my memory had held onto the great battle between good and evil as represented in the noble lion Aslan, and the cruel White Witch, the actual force which propels the action of the story is the character of Edmund. Edmund, the third of the siblings, is something of a brat. He is mean to his younger sister, rude to his older sister and he is terribly jealous of Peter, the eldest of the clan. This behavior was disturbing to my son, so I asked him why he thought Edmund was acting like this. He said, “I think because he only wants what he wants.” Exactly. As the story unfolds, we realize Edmund’s brattiness stems from an almost complete and total focus on himself. It is this self-centered focus, more so than the inevitable clash between good and evil, which is the driver of the drama, with some dire consequences.

This, I realized, was one of Lewis’s most important narrative choices. For if he was truly trying to make his story a Christian allegory it was essential for him to include the issue of sin; both the causes and the consequences. Sin is a Christian word that has taken on many shapes and forms over the years, and I would argue that much of what we call sin is actually the downstream consequences of our primary, some might say, original sin. Now that term also has a complicated history. It does not come from the Bible. It comes from St. Augustine. Augustine believed human beings were born with an inherent desire to do bad things and that we must be always on guard against that fundamental aspect of our human nature. I have much respect for St. Augustine but I disagree with him on this point. I don’t think our original sin has to do with our inherent desire to do bad things. I think has to do with our inherent desire to want to put ourselves at the center of things and that then leads us to do bad things. Self-centeredness is our original sin. As the ancient wisdom of Sirach reminds us, “The beginning of pride is to forsake the Lord” for when we do that, “the heart has withdrawn from its maker.” And the result of this self-centered shift in our focus, will not only be pride but also a whole host of other “abominations.”

Like Sirach, I believe that much, if not all, of what we call “sin” stems from this primary misstep: to think first, and often only, of ourselves; to seek out the seat of highest honor; to see the world through the lens of how everything affects me, what is good for me, what do I want, what do I deserve, what should I get? The result of this self-centered focus is a person who is increasingly out of touch with the world. Like Narcissus locked in a stare at his own reflection they are unable to connect with anything beyond themselves. Such a soul becomes necrotic, eating away at itself, withering. This can often lead to bitterness, envy, a lack of compassion or curiosity. It results in a hardness of heart that is ugly – and sad. Even more disastrous are the ripple effects of this kind of self-centered approach to life. It allows us to use other people, manipulate them like pawns, for our own self-amplification. This leads to conflict and strife, to jealousy at others’ success and pleasure in others’ misfortune. Greed, arrogance, cruelty, all have their roots in a self-centered approach to life. And this inclination for us to focus on and prioritize ourselves above others has been the predominant narrative of humankind since (almost) the beginning.

And then came Jesus. Who came with strength, and bravery, and wisdom, but even more importantly, with humility. And in so doing he showed us that a good life, a holy life, a righteous life is one that is other-centered, not self-centered. “For all who exalt themselves will be humbled, and those who humble themselves will be exalted.” Jesus said this because when we step aside, out of our own spotlight, we make room for something else, someone else to step into it: God. Maybe God will come as one of those strangers we entertain, who turn out to be angels. Maybe God will come as one of the poor, the crippled, the lame or the blind you invite to your table, like Jesus tells us to, instead of the rich fancy folks you want to get in good with for your own advancement. Maybe God will come as a teacher or mentor who speaks a Word of wisdom to you. Maybe God will come some other way, but God will not come if you are standing in His spot. Because a self-centered life results in a self-centered faith which means there is no room for the revelation of God to move in. To step aside, in heart and mind, and leave a space at the highest place of honor, that is the antidote to our original sin, that will puncture our pride and return us to right relationship with God and just as importantly with one another. It will revive our compassion—a word which literally means to “suffer with” so that, as the Letter to the Hebrews exhorts us, we might actually “remember those in prison as if you yourself were in prison…remember those who are tortured as if you yourself were being tortured.” Such an other-focused approach to life will also expand our joy because then we rejoice not only at our own good fortune, but at the goodness and gifts enjoyed by others. And finally, an other-centered approach to life, is the only way for us to be open to love, a virtue that cannot exist in a self-centered soul, for it only blossoms when someone beyond ourselves is at the center of our heart.

This, I realized on this latest trip back through the wardrobe, is why Edmund is such a critical character to the Narnia narrative. Because he dramatizes the dangers of the human condition and our predilection for self-centeredness. As the story goes along, he becomes more and more alienated from his siblings, becomes even more cruel and spiteful, and is exploited by the evil one. His selfishness has consequences he can’t even foresee because he can’t see beyond himself. It is only late in the book, when he witnesses the White Witch turn to stone a party of innocent creatures celebrating Christmas morning that he understands just how far he has fallen. And it is at that moment, Lewis writes, that “for the first time in this story [Edmund] felt sorry for someone besides himself” (117).

Now, I won’t spoil the ending, but as the book draws to a close, it becomes clear that the only way to save Edmund from the White Witch’s power, to pull him out from himself, and to restore him to right relationship with those he loves, is through an act of such humility, such supreme sacrifice, an act of such self-lessness, that it shocks the system, and saves his life. This story is our story. Our propensity to focus first and foremost on ourselves is so deeply engrained in us it feels “original” to our being. And it is at the root of much of the problems of humanity. That has been the same yesterday, and today, as it will be forever. But thankfully, as Edmund had Aslan, we have Jesus Christ who is also the same yesterday, today and forever: the one who humbled himself to the point of death, even death on a cross, that he might save us from ourselves; that he might show us, through an act of such supreme selflessness, that when others are at the center of our heart, when there is space God is at the center of our soul, then all our sins, even the original one, can be washed away.