The Rev. Noah Van Niel

Christ and St. Luke’s

October 16th, 2022

The Feast of St. Luke: Sirach 38:1-4,6-10,12-14; Psalm 147:1-7; 2 Timothy 4:5-13; Luke 4:14-21

Today we celebrate the Feast of St. Luke, which is known in The Episcopal Church as our “patronal feast” or our “Feast of Title” since we bear St. Luke’s name in ours. (As I wrote in the Friday email the Episcopal Church does not designate a specific day to celebrate “Christ” which is the other half of our parish’s title, but I would argue that every Sunday is feast of Jesus Christ, and therefore we are sufficiently covered.) Like any feast day, today’s service is a celebration! But it’s also an opportunity for us to reflect on the life of a particularly faithful individual and see what they might have to teach us as we seek to live faithful lives of our own. And St. Luke gives us much to ponder.

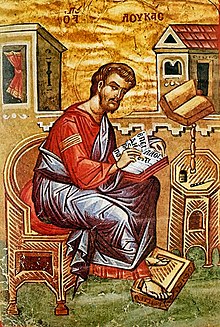

Like all the people in the Bible, Luke remains something of an enigma. There is a man named Luke mentioned in a few of the epistles –or letters—of the New Testament. He was a loyal follower of Paul’s travelling with him around the ancient world in the 50’s and 60’s AD. This Luke is referred to as the “beloved physician,” which is why he has long been honored as the patron saint of doctors, nurses, and healers of all kinds. Then we also have the Gospel of Luke and its sequel, The Acts of the Apostles, written sometime between 75-90 AD. Together these two books account for over 25% of the entire New Testament, which is the largest contribution by a single author. Tradition—meaning the teachings of the church leaders in its early centuries—attributed this Gospel and the Acts of the Apostles to Luke, the beloved physician, giving them his name. However, there is nothing in the Gospel or Acts themselves which directly confirms or refutes this attribution. All the author says about himself is that he undertook to write a new and more complete story of the life of Jesus after reading previous accounts (most likely, Mark) and doing his own independent study. So, the text does not allow us to say for sure that the Luke mentioned in the epistles is also the author of the Gospels and Acts. It’s possible. But uncertain. Tradition also states that Luke was an artist because there are long-believed, but unsubstantiated stories that he painted the first pictures of Mary and Jesus, so the creative arts get added to his muddled, fascinating biography. So then, what are we to make of blessed Luke: physician, artist, evangelist? Well, I would argue that even though we will never be able to definitively prove that these three roles coexisted in a single man, the fact that they have become components of who we conceive of St. Luke to be is important, for combining them together yields some essential insights and understandings about what it means to be a follower of Jesus Christ.

Let’s start with Luke the physician. As our first reading makes clear, physicians held a distinguished position in ancient society. Even if the externalities of the profession bore little similarity to the field today the heart of the matter is the same: they were meant to help, and to heal, and to sustain life. In this way, Sirach says, they are God’s instruments, and their skills are sacred. I believe that remains true, for regardless of one’s faith convictions, medical professions are one of the few careers entirely devoted to the well-being of another. And that is a sacred orientation to have toward the world. As a physician then, Luke would have shared this sacred orientation and lived a life devoted to helping and healing those in need. What also remains true today, is that even in those early days of the common era when Luke was living, the role of the physician was, in many respects, an apolitical one, meaning the physician’s first commitment was to heal the person before them regardless of who they were or where they were from. This was a foundational ethic of the field, and it has remained so through the ages. As the great 19th century microbiologist and father of modern medicine Louis Pasteur (who graces our nave as a statue right up there) once said, “One doesn’t ask of one who suffers: what is your country and what is your religion? One merely says, you suffer. This is enough for me. You belong to me, and I shall help you.”

Pasteur’s words sound almost like a sermon on the parable of the Good Samaritan, don’t they? And interestingly, that parable occurs in—and only in—the Gospel of Luke. Remember one of the key points of that story is that as a Samaritan (who were the longtime rivals and enemies of the people of Israel) there was no social or political expectation for the man to stop and help the Israelite by the side of the road. The crossing of the socially constructed boundary was part of the shock and the point of the parable. But he did so because the man was suffering and that was all that mattered. That was Jesus’ point in telling it. Such boundary crossing happens repeatedly in the Gospel attributed to Luke and in the Book of Acts. If these books can be said to have an agenda, it is this: that Jesus came to bring good news to all people—Jews AND Gentiles. And interestingly, all the notable instances of Gentile inclusion in the Gospel attributed to Luke have healing at their center. Just last week we had an example of this with the story of the ten lepers who Jesus heals and only one returns to give thanks. Remember what it said about that one? He was a Samaritan. And yet Jesus commends his faith, a blesses him on his way. Over and over in this Gospel, Gentiles come to Jesus in faith, and they or their loved ones are healed. Now, keep in mind, the inclusion of Gentiles into the covenantal relationship with God was a huge shift in the understanding of the time and it was a major point of contention in the early church. But Paul eventually persuaded the Apostles that the opportunity for a relationship of closeness with God that was previously the purview of only a few, should now, through Jesus Christ, be open to everyone. And I find this aspect of the Gospel of Luke and the Book of Acts—this expansive and inclusive understanding of Jesus’s message as manifested through acts of healing—to be the most compelling argument that Luke the physician, was the writer of the Gospel that bears his name. For it would make sense that a man who was trained to offer help and healing to anyone in need would understand that Jesus came to do the same, especially if that person had travelled around with Paul, who was the greatest advocate for this expanded understanding of who Jesus’ message was for.

But what of Luke the artist? How might he fit into this picture? Well, just as medicine is inherently focused on the benefit of the other, and makes no distinctions of who that other is, I would argue that the arts share a similarly expansive and inclusive mindset. Art becomes art when it is shared. Writing with no reader in mind is journaling. Drawing with no viewer in mind is doodling. Singing with no one to hear it is practicing. What makes art, art, is the creation of something which others—regardless of who they are—will encounter. And when they do, it will evoke something in them: a thought, a feeling, a reaction that fosters a moment of connection between human beings which can bring inspiration, insight, and sometimes, yes, even healing. Back in 1983, the scholar Lewis Hyde wrote an eloquent book called, The Gift, that quickly became a classic for exploring the nature of art and the act of creating it. In the book, Hyde says that the true test of a work of art is what it sparks in us as we take it in. He writes, “Sometimes then, if we are awake, if the artist really is gifted, the work will induce [in us] a moment of grace, a communion, a period during which we too know the hidden coherence of our being and feel the fullness of our lives.” (196). Communion, coherence, fullness, these are the gifts that art offers us, and they are spiritual gifts that can heal the soul, much the way a physician can heal the body. If medicine is concerned with sustaining life, art is concerned with enriching it, and both take as their primary position an encounter with the other and make no distinctions of who that other could or should be. Whether Luke was both artist and physician we do not know for sure, but it is not so strange as we might think for these two professions to be brought together in him. For both share an external gaze that seeks to offer something helpful, be it beauty, or healing or wholeness to all.

And this is the very same story the Gospel of Luke and the Book of Acts are trying to tell about Jesus. If we still have any question of that, we need look no further than that dramatic scene at the synagogue in Nazareth which we just heard. This is Jesus’s first recorded moment of public ministry, andserves as a summation of how Luke understood what Jesus was all about. After his baptism in the Jordan and his temptation in the wilderness Jesus has come home. And on the Sabbath, he makes his way to the local synagogue, as was his custom. He stands up to read and is handed the scroll of the prophet Isaiah. He unrolls it and searches the text for a specific passage. It takes him a moment to find it, but when he does, he reads out for all to hear: “The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to bring good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovery of sight to the blind, to let the oppressed go free, [and] to proclaim the year of the Lord’s favor.” And when he is done, he rolls the scroll back up, gives it to back to the attendant and sits down. And then he says one more thing “Today this scripture has been fulfilled in your hearing.” And as Luke goes on to tell us, it was. Through miracle and parable, at meals and at roadsides, from Bethlehem to Jerusalem, from crowded manger to empty tomb, this message of healing, and hope; of release, and relief; of lightness and life and love; not for the few but for the many; not for some, but for all, that was for blessed Luke—physician, artist, evangelist—the point and purpose of Jesus; that was Christ for St. Luke. As we seek to be worthy of both those names, may it be so for us as well.