The Rev. Noah Van Niel

The Chapel of the Cross

August 30th, 2020

Proper 17 (A—Track 1): Exodus 3:1-15; Ps 105:1-6, 23-26, 45; Romans 12:9-21; Matt 16:21-28

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore—

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over—

like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

–Langston Hughes, Harlem

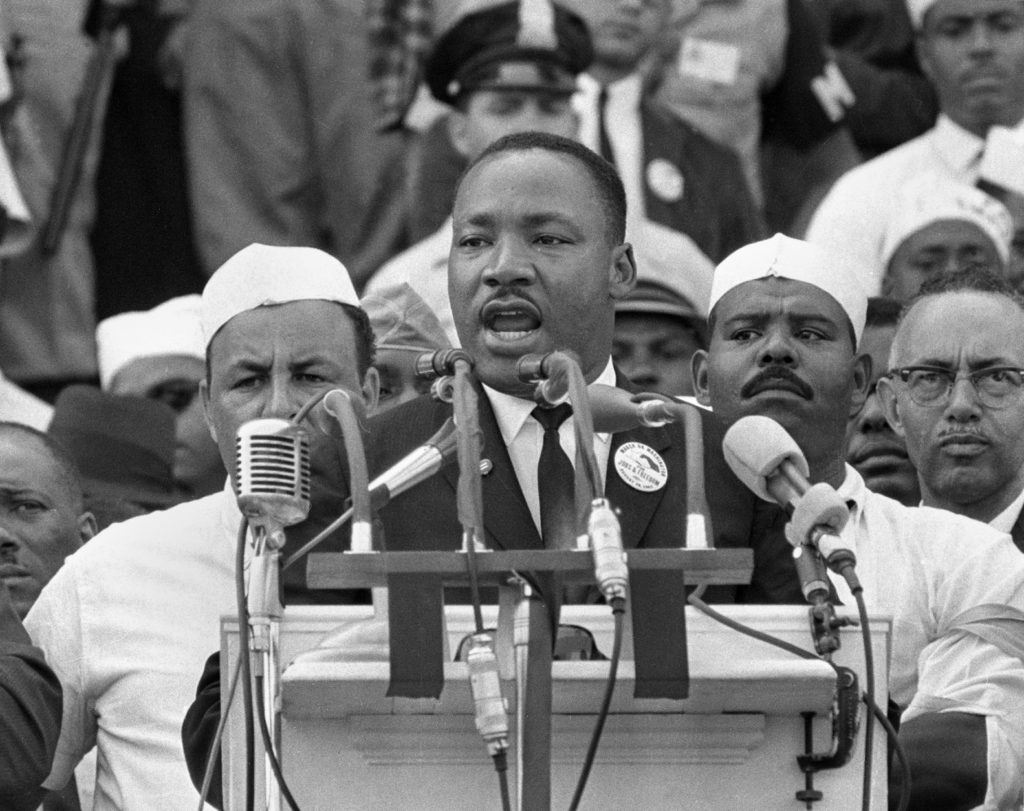

This past Friday, August 28th, marked the 57th anniversary of the March on Washington and Martin Luther King’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech. Normally, 57 is not a particularly notable anniversary to mark but this year we had considerable cause to pause and ponder anew that memorable dream and how it has and has not come to fruition. As news of a police officer shooting into the back of a young black man named Jacob Blake reignited protests and marches across our country—from small town Wisconsin, to the nation’s capital, to the worlds of professional sports—we were forced to grapple again with issues of race and justice; violence and fear. Jacob Blake’s case is a complicated one, but one thing that is clear is that he did not deserve to be shot seven times in the back. What is also clear is that the week of protests that followed were not just about him. They were about him, but not just about him. Now, in what has become the summer of our discontent, we are seeing the explosion of a dream deferred. The dream of racial harmony and equality so memorably defined by Dr King in his speech so many years ago and still so long in coming.

What King didn’t say in his “I Have a Dream” speech but what he spent much time writing on and preaching on elsewhere, was just how we were going to get there, to that promised land he could see from the mountain top of his mind’s eye. But given the escalation of aggression and violence on the fringes of some of these protests and the responses to them, it’s worth remembering that according to Dr. King, it was love that was going to lead us to that promised land.

King wasn’t always convinced of this though, he had to be converted to the idea that love could actually accomplish the hard work of social change. In 1960 he wrote that early in his career, “I had almost despaired of the power of love in solving social problems…I felt…when racial groups and nations are in conflict a more realistic approach is necessary.” It was at that point in his life that King came upon the work of Mahatma Gandhi and his effective use of non-violent resistance to help the Indian people win independence from the British. King became fascinated with the Gandhian principle of satyagraha. He writes:

“(satya is truth which equals love, and graha is force, satyagraha thus means truth-force or love-force) [this] was profoundly significant to me. As I delved deeper into the philosophy of Gandhi my skepticism concerning the power of love gradually diminished and I came to see for the first time that the Christian doctrine of love operating through the Gandhian method of nonviolence was one of the most potent weapons available to oppressed people in their struggle for freedom…This principle became the guiding light of our movement. Christ furnished the spirit and motivation while Gandhi furnished the method.”[1]

What this meant, is that for King, effective, lasting social change had to have a spiritual component. Successful social justice movements are founded on the power of the soul, not just the power of the state. Laws and policies and practices can be changed, but they would be empty and fleeting changes if they were not anchored by something deeper. And that is why the Church, and our church, has an essential role to play in the work of racial justice and reconciliation. Because we hold to a belief in and commitment to the “Christian doctrine of love” and are called to equip and empower people to show forth that love not only with their lips but in their lives.

This has long been the church’s call; it is not just a recent phenomenon. That is what Paul is urging the Romans to do in our Epistle this morning. His words capture the same spirit of satyagraha that Gandhi and King were promoting. “Let love be genuine. Hate what it is evil, hold fast to what is good…if your enemies are hungry, feed them; if they are thirsty, give them something to drink; for by doing this you will heap burning coals on their heads. Do not be overcome by evil, but overcome evil with good.”

It is important to clarify what Paul means when he says “evil,” here. Etymologically, it is that which causes pain or trouble for others. It is not the person or people who perpetrates the act, your “enemy,” as it were. According to Paul your enemy is to be loved and provided for. It is the system and the evil actions it produces that are to be abhorred. This is an important distinction and one King upheld as well. “The nonviolent resister,” he explained, “seeks to attack the evil system rather than individuals who happen to be caught up in the system…the struggle in the South is not so much the tension between white people and Black people. The struggle is between justice and injustice, between the forces of light and the forces of darkness.”[2] That is why you love your enemy, because in doing so you affirm and appeal to your bond of common humanity, seeking to awaken in them the deep stirrings of compassion, contrition, and conversion. Those are the burning coals that are heaped on their head. Again, Dr. King,

“{So}…the nonviolent resister does not seek to humiliate or defeat the opponent but to win his friendship and understanding…The aftermath of violence is bitterness. The aftermath of nonviolence is reconciliation and the creation of a beloved community. A boycott is never an end within itself. It is merely a means to awaken a sense of shame within the oppressor, but the end is reconciliation, the end is redemption.” [3]

That happy ending can be a long time coming though. The way of love will test our patience and our resolve. We will be tempted to take short cuts like using violence or exacting revenge. But there’s no future there, only an escalation of bitterness and enmity. We’ve seen evidence of that already this week as a 17-year-old boy came to counter protesters with his automatic weapon and ends up killing two of them. No, as slow and frustrating as it is, as King and Paul remind us, real, substantive, lasting change cannot come from violence or vengeance. It comes from conversion not coercion. And we are converted through love. The love of God shown through us in our lives. In the New Testament the Greek word used to capture this kind of love is agape. That’s the word Paul uses when he says “Let love be genuine.” According to King, this was the kind of love that satyagraha was founded on. A deep moral swell that connects us to the heart of the Almighty. He writes, “agape is understanding, creative, redemptive good will for all…it is the love of God working in the minds of men. It is an overflowing love which seeks nothing in return.”[4] Agape was also the word Jesus used when he talked to his disciples about how we should love one another. It was the kind of love he lived: universal, redemptive, overflowing, self-giving not self-seeking. Peter wasn’t having it, he wanted that shortcut, he wanted to fight. He wanted his Messiah to be a conquering hero not a suffering servant. But no: “Get thee behind me Satan!” Jesus rebukes. That is the way of humanity. That is not the way of God. That is not the way of the cross. That is not the way of love. The way of love is more challenging—“If any want to become my followers, let them deny themselves and take up their cross and follow me”—but it is ultimately more rewarding: “For those who want to save their life will lose it, and those who lose their life for my sake will find it.” This is what discipleship looks like: a commitment to agape, no matter how hard it gets or how long it takes.

You may have caught wind by now that our parish theme for the coming year, the lens with which we will be approaching many of our programs and activities, is “Love Dwells Here.” This is both pronouncement of who we are and a pledge for what we hope to be. We are a Christian community that believes Christianity is founded on love, therefore our Church is a place where love dwells and we want the world to know it. But it is also a mission statement, a challenge to live up to. If love dwells here, and if that love is truly to be genuine, that means nothing less than agape will do. Nothing less than universal, self-giving love, the love of God will do. So long as the evils of racism run rampant all around us, so long as millions of dreams continue to be deferred by violence and oppression, then we have more work to do in fostering, sustaining and sharing that kind of love in our own hearts and in the heart of this community. Our goal is for each of us to be able to stand up, raise our hand and say “love dwells here.” And mean it. And live it. For that is the only way forward as we march toward Dr. King’s dream. So, we are going to spend a lot of time this fall looking internally and externally at issues of race and justice. Because as those who have chosen to take up our cross and follow Christ, we hate what is evil. And racism is evil. But we shall overcome it with good.

[1] King, Martin Luther, Jr. I Have a Dream: Writings & Speeches that Changed the World. Ed. James M. Washington. HarperCollins New York, NY 1992, p. 58-59

[2] Ibid, p. 31

[3] Ibid , p. 30-31

[4] Ibid , p. 31-32